On Tuesday, the state of Missouri lynched Khaliifah Marcellus Williams, who was falsely accused of murdering a white woman. This accusation, of course, has a long history rooted in anti-Black racism; it is this country’s preferred pretext for the brutal social ritual of spectacle lynching and the death penalty as an extension of it. The death penalty is not only state-sanctioned lynching, as in cops protecting, promoting, and participating in vigilante violence; it is straight-up-state lynching.

The incontrovertible evidence proving Williams’s innocence is irrelevant to the point. What’s relevant is why anyone would trust a political process vested with the godlike power to determine who can live and who can die. Guilt is a game of smoke and mirrors. The determination of innocence condemns all the indeterminate. What’s important here is that, as Joshua P. Hill writes:

First, to stop the slaughter we must know. We must know and understand that the killing of Khaliifah Williams was not the flailing of a broken system but the churning of a system working as designed.

In the context of abolitionist pedagogy, Meghan G. McDowell and I ask elsewhere: Why do we kill people who kill people to show that killing people is wrong? Of course, this question can be posed another way, given the structuring logic of anti-Black racism in the carceral psyche: Why do we kill people who haven’t killed people to show that killing people is right? This question isn’t rhetorical; the answer is obvious.

As just one well-known example of this bloodstained history, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, who by their own admission sadistically murdered Emmett Till in 1955, were acquitted by a jury of other white men on the basis of Carolyn Bryant’s fabricated testimony, sutured as it was to the symbolic function of white womanhood to literally reproduce the nation, and in so doing maintain the hegemony of anti-blackness, which is to say, whiteness—a murderous innocence invested with the power to define and so to destroy those presumed guilty by default. Smoke and mirrors.

As long as there is a state that executes mass murder, as long as its violence is considered “legitimate,” there is no justice.

And there is no peace—except in our impartial, always inadequate attempt to bear and lay bare our broken hearts through art and poetry, to act in concert with that language despite and because of our brokenness. But we try. We write. We gather. We protest. We dream. We cry: Rest in peace and power, Khaliifah Marcellus Williams.

Any attempt to express the magnitude of collective brokenheartedness, from Gaza to the Golden Gulag, feels insufficient to the depth of sorrow always in excess of its enumeration. When prose fails us, a beautiful broken-hearted grammar, one that leans into impossibility by stretching language like a throw blanket over freezing feet, can get us closer.1 In “A Martyr is not a Logo,” Neema G. Siphone poetically bridges the distance between the dead and the living, revealing the luminous intimacies of this celestial convening in past as/and future prophecy:

June Jordan wrote apologizing to all the people in Lebanon and from heaven she is still apologizing.

I imagine she welcomed Khaliifah with a warm embrace

The two cloaked in the kind of integrity that the afterlife was made to reward

An integrity undeterred

A martyr is not a logo and certainly not an excuse.

I want to quote Siphone’s beautiful broken-hearted elegy in full, but instead I will strongly recommend you follow the link to read the entire post, which includes poems by June Jordan and Marcellus Williams along with an insurgent archive of remembrance and commemoration against historical erasure.

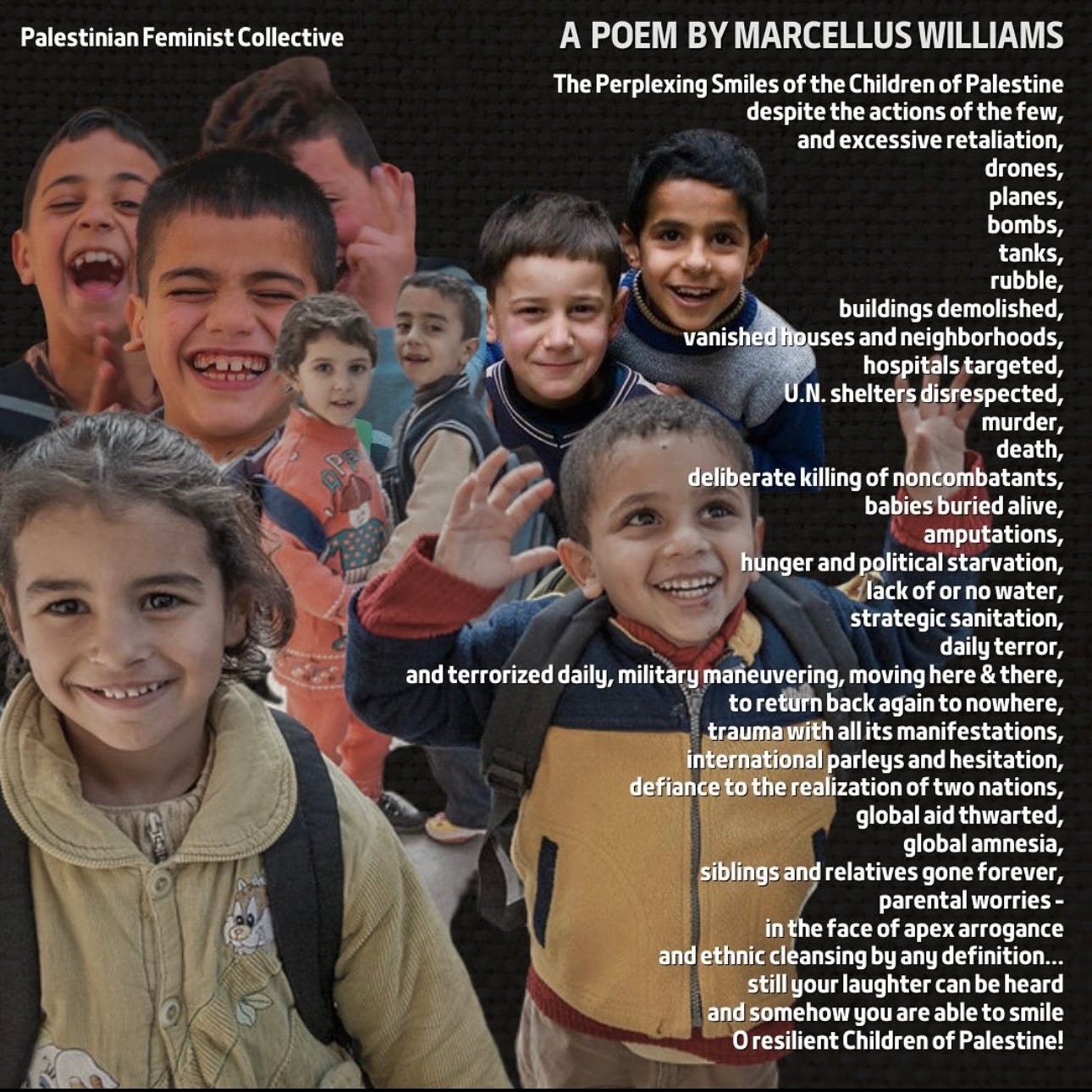

Before you go, though, I want to share one of the last poems Marcellus Williams wrote before his execution, “The Perplexing Smiles of the Children of Palestine.”

Khaliifah’s poem spurns the violence authorized by, to cite his words above, “global amnesia.” This turn of phrase recalls James Baldwin’s warning, in “An Open Letter to My Sister, Angela Y. Davis” (1970): “If we know, and do nothing, we are worse than the murderers hired in our name.” He continues:

If we know, then we must fight for your life as though it were our own—which it is—and render impassable with our bodies the corridor to the gas chamber. For, if they take you in the morning, they will be coming for us that night.

Therefore: peace.

The genocidal machinations of global racial capitalism, in other words, and in grossly disproportionate ways, threaten to trounce and ultimately obliterate everyone and everything. This is why community organizers understand action must originate not from a paternalistic place of “helping” but from a sustained reckoning with mutuality—that what harms you, harms me, but not analogously.2 Baldwin is not talking about self-interest but self-transformation that deepens collective commitments to dismantle the death machine and rebuild social life anew. As antidote to the spiritual void of psychic investments in maintaining the deadly status quo, attended by a permissive amnesia and apathy, Baldwin reminds us time and time again to honor, in practice, the sacredness of our inextricable interrelation. The bottomless grief, too. Hearts breaking like breathing. Sometimes the weight of it feels unbearable, impossible. And yet.

With faith and tenderness, Khaliifah Marcellus Williams’s poetry models this practice of cultivating sacred connection amidst incalculable suffering. To be clear, in a capacious literary tradition of political prisoners, Williams unflinchingly critiques what Ruth Wilson Gilmore defines as “organized abandonment” and “group-based vulnerability to premature death.” At the same time, his poetry resurrects and resounds with a defiant joy he affirms in the smiles of Palestinian children, an inextinguishable fire born of social relationships and global solidarities that persist in spite of and apart from the state’s systematic attempt to annihilate them.

♡♡♡

This phrasing intends to embed a critique of the ableist, xenophobic implications of the term “broken grammar.”

This is why the misguided thinking connected to the fallacy of “reverse racism” and men’s rights activism is so harmful. There is a crucial distinction between feelings of prejudice, acts of discrimination, and systems of oppression, such as racism, sexism, classism, and ableism. To conflate individual emotions with institutional structures of power is at best an insidious ignore-ance of the scope and stakes of that power: life and death. In other words, those structures coalesce to drastically impact life chances and choices through ideological and repressive state apparatuses, including but not limited to education, media, law, the courts, cops, prisons, politics, administration, and public policy. Generative conversations about personal prejudices and discriminatory practices must be situated within an understanding of interlocking hierarchies that combine to violently accrue unearned advantages to one social group over and against another, again and again and again.